Physical Risk: how a sole focus on climate leads to structural blind spots

Introduction

Physical climate risk assessments are now a core component of financial risk management, driven by regulatory expectations (e.g. TCFD/ISSB) and increasing losses from climate-related hazards. These assessments typically focus on hazard–exposure–vulnerability relationships associated with acute events (floods, heatwaves, storms, wildfires) and chronic changes (sea-level rise, temperature increases, water stress).

However, most physical climate risk frameworks remain infrastructure- and asset-centric, modelling climate hazards largely in isolation from the natural systems in which assets and economic activity are embedded. As a result, they often assume static baseline conditions for land, soils, ecosystems, and biodiversity, implicitly treating nature as either irrelevant or exogenous to risk outcomes.

This creates a structural blind spot: natural capital and biodiversity fundamentally shape how climate hazards translate into real-world financial impacts.

Why a sole focus on climate isn’t enough

Natural capital, including ecosystems such as forests, wetlands, mangroves, coral reefs, soils, and watersheds, plays a critical role in modulating physical climate risks through ecosystem services such as:

- Flood attenuation and water regulation

- Coastal protection from storm surge and erosion

- Temperature regulation and urban heat mitigation

- Soil stability and landslide prevention

Biodiversity underpins the resilience and functionality of these ecosystems. More diverse systems are generally better able to absorb shocks, recover from disturbance, and maintain service provision under changing climatic conditions.

Ignoring natural capital and biodiversity, therefore, leads to systematic mispricing of physical risk, because:

- Degraded ecosystems can amplify climate hazards and associated damages.

- Intact or restored ecosystems can mitigate hazards, reducing losses and recovery costs.

- Ecosystem degradation can introduce non-linear tipping points, where small climatic changes trigger disproportionately large financial impacts.

Nature in action: the power of mangroves

Mangrove forests function as highly effective natural coastal defences, attenuating wave energy, reducing storm surge heights, and limiting coastal erosion. Empirical studies show that intact mangrove systems can reduce wave heights by up to 60–70% over relatively short distances, while also lowering inland flood depths during cyclonic events. As a result, mangroves materially reduce both the probability and severity of coastal flood damage.

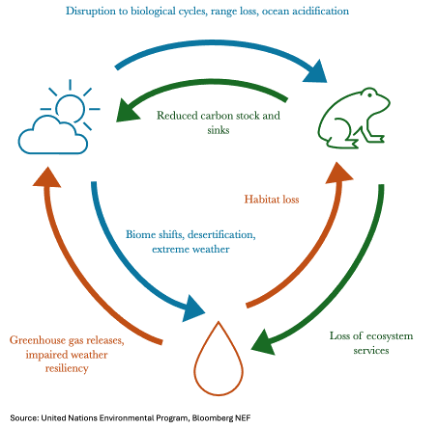

When comparing two tropical storms of broadly similar intensity, Cyclone Seroja (Indonesia) and Hurricane Isaias (Atlantic), the resulting financial impacts differ substantially. Cyclone Seroja was associated with approximately US$236 million in reported losses, whereas Hurricane Isaias resulted in an estimated US$3–5 billion of insured losses in the United States.

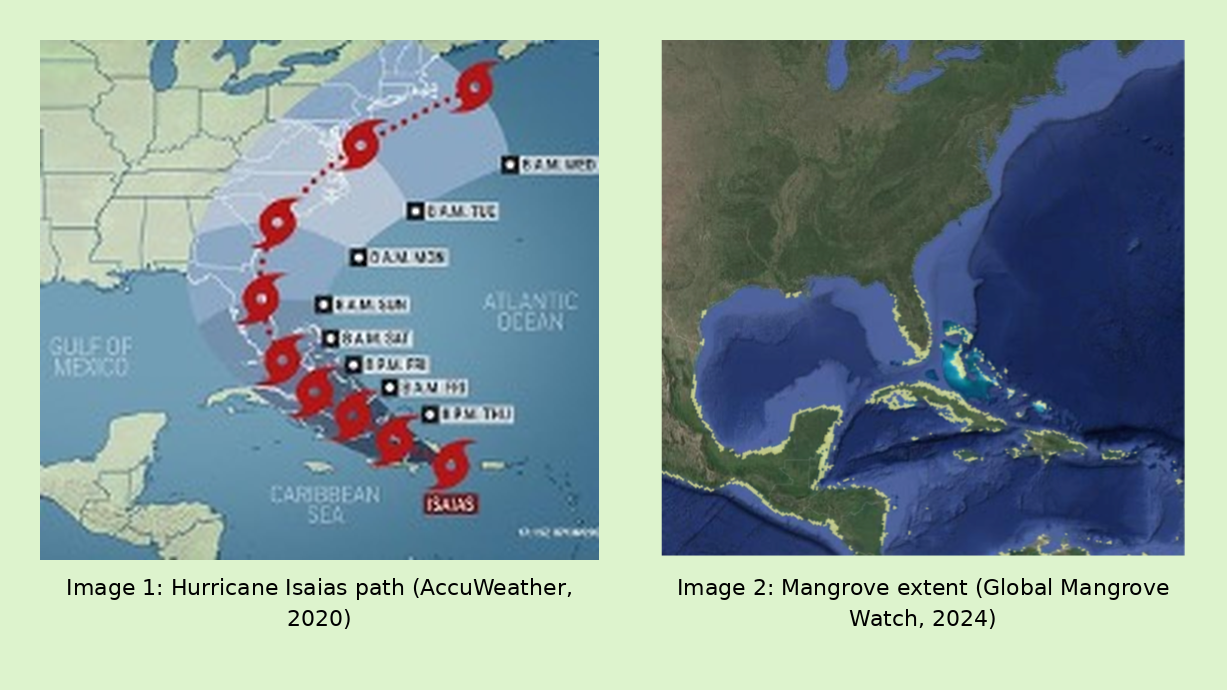

This comparison must be interpreted with important caveats. Indonesia has a significantly lower concentration of insured and high-value coastal assets, which contributes materially to the observed difference in losses. However, evidence suggests that damages in Indonesia would likely have been considerably higher in the absence of its extensive mangrove coverage. Mangrove forests along affected coastlines played a meaningful role in reducing wave energy and flood depths, thereby mitigating potential damage.

Supporting this, a World Bank Indonesia study on the economics of mangrove ecosystems estimates average benefits of approximately US$15,000 per hectare per year, with values reaching up to US$50,000 per hectare per year in areas protecting high-risk or high-value coastlines. A substantial portion of these benefits is attributable to avoided flood and storm damage.

This is further supported when we look at the fallout from Hurricane Isaias. From the National Hurricane Centre (NHC) report can see the states where the majority of the economic damages occurred ranged from the Mid-Atlantic to New England. According to the NHC (2021), approximately $3.5bn of the damages occurred in these areas, compared to $1.3bn outside of the Northeast, where there was a lower density of valuable coastal assets, but also increase mangrove presence (as indicated by the yellow zones on Image 2).

Taken together, these examples illustrates that two events of roughly comparable intensity can result in vastly different financial outcomes, driven not only by exposure and asset values, but also by the presence, or absence, of natural capital. In Indonesia’s case, mangrove ecosystems materially reduced physical climate risk and associated economic losses, underscoring the importance of incorporating natural capital into forward-looking physical risk assessments, while the opposite can be seen in the case of the USA.

Integrating nature isn’t “additional” it is essential for accuracy

Incorporating natural capital and biodiversity into physical climate risk assessments is not an environmental “add-on”; it is a core financial accuracy issue. It affects:

- Asset valuation and depreciation assumptions

- Insurance pricing and availability

- Credit risk and long-term solvency

- Capital allocation between grey and nature-based adaptation

As climate impacts intensify, the interaction between climate hazards and ecosystem condition will increasingly determine loss severity. Institutions that fail to account for this interaction risk systematically underestimating exposure and misallocating capital.

Physical Risk: how a sole focus on climate leads to structural blind spots

Natural capital and biodiversity fundamentally shape how climate hazards translate into real-world financial impacts.

.png)

.jpg)

.jpg)